It’s that time again… First Friday is here! While there are tons of excellent options around Indy, we highly recommend checking out the opening of Living Threads at Tube Factory artspace. Docey Lewis, a textile artist currently based in New Harmony, Indiana, will reveal her latest work that centers around extinct and endangered species. Living Threads draws attention to the environment, and our ability as humans to change it for better or worse.

The exhibit opens at 6:00 p.m. and will run through December 11th. The exhibit is a part of Big Car Collaborative’s ongoing Social Alchemy project. This project explores utopian societies and utopia influenced works and places.

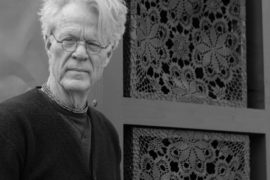

In our Vol. 21 print magazine, Phillip Barcio writes about Lewis’s life as a textile artist and where her work has taken her, as well as how she ended up in the serene town of New Harmony. Here is the story:

It’s winter, late-pandemic. I’m in my home office perusing images of handwoven textiles by an artist named Docey Lewis. In her 70s, Lewis stepped away from her successful global textile business to restart the art practice from which she walked away in her 20s.

Glancing away from Lewis’s delightful abstractions to the headlines on my muted TV, I see that a million Americans are now dead from COVID-19; six million dead worldwide; Russian troops are fighting Ukrainian citizens in the streets; and somehow 45 is back on the news, calling some petty dictator a genius.

Optimism is in short supply. Yet, turning back to Lewis’s rugged, elegant, geometric compositions, I see something in their patterns and interconnected layers that suggests a beautiful, Bauhaus-ian dream—a better world run on systems designed by artists, not authoritarians.

I’m one of those people—the ones who think abstract art is inherently political, because it opens doors of perception that increase conceptual literacy, or something like that.

Wondering if she is of the same ilk, I give Lewis a call. She is, after all, uniquely qualified to speak about the intersection of politics and abstract art—not only because she’s an abstract artist, but because she’s descended from the founders of one of America’s earliest Utopian societies: New Harmony, Indiana.

Originally called neu Harmonie, the city was established in 1814 by Johann Georg Rapp, leader of an end-times cult from Pennsylvania. Rapp’s followers built 180 structures and established a thriving economy, but by 1825, the second coming having failed to come, they moved on, selling the town to a wealthy industrialist named Robert Owen—Lewis’s great-great-great-grandfather.

Owen attempted to establish a second Utopia in New Harmony, this one based on the principles of universal education and equality. His sons joined him. One, Richard Owen, was the first President of Purdue University. Another, Robert Dale Owen, was elected to Congress, and introduced the bill establishing the Smithsonian institution.

Despite their means and influence, the Owen family, like the Rapps before them, saw their Utopia fail. In Robert Dale Owen’s autobiography, he postulated that Americans don’t naturally want to work together; particularly those who came to the United States after leaving structures where they were trapped.

Like her abstract textiles, Lewis has a tangled relationship to both perspectives—the one that thinks structures can and should be constructed that will foster harmonious relationships, and the one that prioritizes independence.

“For me, Utopia is kind of a squishy word,” Lewis says.

The original Greek ou topos literally means no place. There’s a metaphor there I guess.

“The work I do is about creating structures on which pictures might exist,” she explains.

Doesn’t that relate to everyday life, I ask?

“Every day is a new opportunity to help make other people’s lives better,” Lewis says. “So what structures do you put in place to make that happen?”

Lewis returned to her ancestor’s field of Utopian dreams a few years ago. In an art studio above a bakery in downtown New Harmony, haunted by the ghosts of her successes and her losses, she is trying to make peace with her past while literally pulling at the threads of her personal history.

Lewis’s roots in the woven world reach back to age nine, making potholders in the attic of her family home in Northford, Connecticut. Her first real textile training came while in college at Stanford.

“The university had a Jane Goodall Center, and I’d applied to go to the Gombe Stream Reserve over the summer,” Lewis says. “I was in the middle of that application and I met a man. You know, there’s always a man hidden away in the story when you’re young. I was very conflicted about whether to go to Africa or stay and have this romance. I chose the romance.”

That summer, Lewis enrolled in a weaving class and learned the basics of working with raw fiber.

“I was hooked,” she says with a laugh.

Next thing she knew, she was on a train crossing Canada solo for the Albion Hills School of Weaving, Spinning and Dying. She spent three months there living on a sheep farm and learning the grass roots of the textile process. Edna Blackburn, who ran the school, brought emotionally disturbed children out to the school and had her students show them the basics of the craft.

“They found it was a very calming activity,” Lewis says. “I was exposed to this other aspect of the effect of weaving on a human being’s mental health. I saw that it could be a broader thing than just me playing with a loom and making something with it.”

Lewis then headed south in a VW van to the Ganado, Arizona, Navajo reservation where she learned a different kind of spinning and weaving and experienced the Navajo dye process. Meanwhile, back in California, the man for whom she had given up her dreams of Africa was busy building her a studio in a geodesic dome on a 40-acre property in the redwood forest.

“It had been a bootlegger’s weekend extravaganza,” Lewis says, “kind of falling apart, but cool.”

In that redwoods retreat she built the loom on which she made her first textile artworks. At her debut exhibition, in a library in Redwood City, a collector invited Lewis to do a large private commission for his home.

“He was a mucky-muck in the corporate world in San Francisco,” Lewis says. “So that led to other opportunities. I ended up with an agent, Bridget O’Hara, who was a character. She’d been a chef on a submarine. She was Irish, her son was gay. I met my first transvestite. I was so naive. I broke out of my New England cocoon. It was the early 70s in San Francisco and I was exposed to a very colorful world.”

Looking back to her experience at Albion Hills, Lewis was always looking for ways to make a concrete difference in people’s lives with her work. Wondering if business had a better chance of making a social impact that art, she decided to start her own line of clothing, made from her own fabric.

She enrolled in the San Francisco Fashion Institute, learning to cut and sew handmade fabric by day, and attended night school to learn accounting—“just enough to understand a balance sheet,” she says.

Lewis’s first patroness in fashion was Doris Khashoggi. Yes, that Khashoggi.

“She had married the brother of Adnan Khashoggi, the arms dealer,” Lewis says.

After her divorce, with her fortune Khashoggi set up retail stores in Palo Alto and San Francisco. Lewis was one of several independent clothing designers she took under her wing.

The success of Lewis’s clothing line inspired her to expand by making fabric to sell to other designers. To do that she needed more weavers, so she put together a business plan and took it around to embassies from countries where there were weavers who needed work. Her timing with the Philippine embassy was perfect.

“They were doing a trade mission and they invited me on it,” Lewis says. “March Fong Eu, the Secretary of State of California, headed the tour. Texas Instruments was there looking for overseas production, and little old me with my hand weaving workshop.”

Her second day in Manila, Lewis had breakfast with President Marcos. Soon, she had investors helping her establish a workshop in Baguio.

“Imelda Marcos was one of my best customers,” Lewis says. “She commissioned me to do all the fabrics for the interiors of the summer palace. Kept me busy for years.”

Gradually, Lewis expanded her operations into other countries, including Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nepal. The list of companies that have sold the products made in her workshops includes Sears, Hallmark, Bergdorf’s, Lord and Taylor, Bloomingdale’s, Macy’s, Henri Bendel, Gumps, Horchow, Neiman Marcus, and Sundance Catalog.

The real payoff for Lewis, however, was mentoring the local female weavers she worked with to become entrepreneurs. She also recalls many difficult decisions along the way, and many tragedies, losing friends and colleagues to earthquakes, volcanoes and floods.

Regaled by the tale of her journey from a tiny redwood forest studio to the top of a global design empire, I can’t help but ask Lewis why she walked away; and why she chose the soil of her ancestor’s disappointments as the place to revisit her own sidelined dreams.

Her answer:

“Do you know David Brooks, the New York times columnist? Well, two or three years ago, he started something called the Weave Project. The idea was that our social fabric has come unraveled. Brooks got these dinners going where you would invite your town council member over to dinner and talk about things you have in common, and have a civil conversation and not name call and debase the other side. So I thought, this is a chance to take that metaphor, reweaving the social fabric, and make it real.”

In addition to trying to heal herself through her art, Lewis is involved in an initiative to bring disadvantaged kids from all around to learn weaving in New Harmony. They’ll take classes and see what it’s like to camp and hike and live in a rural village.

“I’ve got selvedge waste of silk wallpaper from a workshop in Nepal, and stacks of samples and lines of products and yada yada, all gathering dust,” Lewis says. “It’s like an archeological dig of everything I’ve ever woven or designed. I thought maybe I could turn it into something—take this detritus, take the stories, take everything, and weave it together and see if I can bring some measure of peace to my own life.”

It isn’t Utopia, but it’s a good yarn.